11 Sep 2025 Alfred Nobel’s Obituary

You may remember that back in June we sent out the Beacon Summer Reading list. It’s something we’ve done the past few years and this summer my selection was “The Mysterious Case of Rudolf Diesel: Genius, Power and Deception on the Eve of World War I.” It’s a fantastic read, but this post isn’t about Mr. Diesel or his engine. Rather, it’s about Alfred Nobel and a short footnote found part-way through chapter 10.

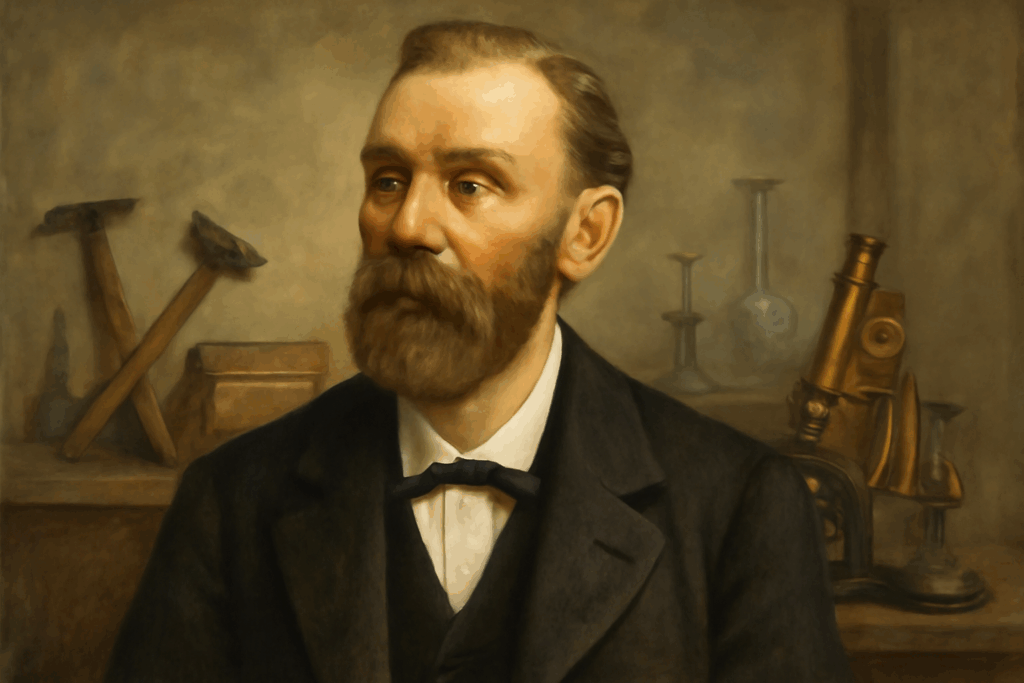

Before getting to what it said, it’s worth noting that Alfred and his two brothers were, in short, impressive. Robert and Ludwig, the first and second born, were pioneers in the oil industry and built the largest oil company the world has ever seen. Alfred invented, among other things, dynamite.

Despite their success, they weren’t without controversy, with Alfred being the most controversial. In fact, his obituary referred to him as the “Merchant of Death” because of the way dynamite revolutionized warfare. Understandably, the Nobel family was incensed by the moniker, with no one in the family more incensed than Alfred himself, who had the chance to read his own obituary because he was not, in fact, dead.

Which leads me to the footnote:

When Ludwig Nobel died in April 1888, French newspapers incorrectly reported the death of Alfred, who was in fact alive and well. Alfred then read his own obituary, which was a scathing critique of his life and work. The obituary named Alfred a “merchant of death” and declared that his invention, dynamite, “killed more people faster than ever before.” Alfred was so disturbed at this potential posthumous reputation that he later changed his last will and testament to bequest his entire fortune to a new foundation that would award a series of prizes to “those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind.”

Thus, the Nobel Prize.

In a less-than-ideal way, Alfred was experiencing something similar to a common therapeutic technique known as the “eulogy exercise.” The idea is you write the eulogy you’d want someone you love–a son, daughter, spouse, close friend, business partner–to read at your funeral, with the goal of fleshing out your core values and aspirations.

This little footnote resonated with me because I went through this exercise a few years ago when I found myself focusing way too much on things that aren’t terribly important. There were nights I’d toss and turn, worrying about the long-term impact of my kids not eating enough vegetables, for example. As I wrote out how I want the kids to talk about me when I pass, it did two things: First, it helped clarify the lessons I want to impart to them, and second, it took some of the pressure off. Is it important Jack and Gwen have a healthy diet? Of course, but what’s more important to me is that I model generosity towards others, love and care towards their mother, and that they know they have my full and undivided attention when they are talking to me. Identify the big stuff, focus on the big stuff, give yourself grace on the rest.

Invariably, this exercise ends up touching our relationship with and treatment of money. My worries about peas and carrots one night may on other nights be about summer camps for the kids, what college they attend, where we vacation, how our car stacks up against what our neighbors drive, or whether or not our house is big enough/clean enough/in the right enough zip code. I am far from how I want to be talked about at my funeral, but the exercise is intentionally aspirational. It’s easy to think we, our spouses, or our kids need “stuff” or that the best legacy we can leave is financial. Without realizing it, society or our social circles can co-opt our goals and make us think we need certain things that, ultimately, won’t make us happy because they aren’t our goals and they don’t grow out of our values.

Alfred’s situation is different than what most of us will experience in that he was a very public figure . . . and he was reading his own obituary. It’s clear that how the world saw him was not how he wanted to be seen, so he did something about it. We can, too.

We may not have the means to create a foundation as Alfred did, but we can create an environment in our lives and within our homes that aligns with our values. It starts with something as simple as putting pen to paper.

The content above is for informational and educational purposes only. The links and graphs are being provided as a convenience; they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by Beacon Wealthcare, nor does Beacon guarantee the accuracy of the information.